In Feral Atlas, everything is entangled. Most projects about the Anthropocene focus on the planetary, from large-scale data modeling to the geological epoch. While valuable, this view overlooks the smaller, distinctive phenomena that make up this larger framing. As Anna L. Tsing notes in The Mushroom at the End of the World, “big histories are always best told through insistent, if humble, details.” 8 In this expansive online atlas, Tsing and her colleagues scale down and gather interconnected vignettes of human and nonhuman entities. Three axes reveal our ecological entanglements: the first, Anthropocene Detonators, focuses on infrastructure through the lens of invasion, empire, capital, and acceleration; the Tippers axis highlights the brutality of this industrial imperialism; the final, Feral Qualities axis underscores qualities of activity that have always developed outside of human control and continue to do so.

Contrary to the commonly held belief that infrastructural projects scale unidirectionally, the atlas illustrates that all transformations become “contaminated” through interaction. Nothing is isolated. Through this interview and guided tour of Feral Atlas, Tsing invites us to navigate her findings. By paying attention, Tsing suggests, we might come to see these contaminated interactions as guides for living. By focusing on the feral rather than the controlled, we can make space for non-designed consequences and begin to understand the ecological effects of human actions. As Tsing says of the project, “This is a story about infrastructural work through which we’ve let the world become unlivable,” and what we can learn from it to survive and hopefully thrive on the conditions that we’ve created for ourselves.

On September 24, 2020, we met with Anna Tsing to discuss Feral Atlas before the launch of the project. Below you’ll find excerpt from that conversation.

— Roxana Fabius, Patricia Margarita Hernández, Mindy Seu

Interview

SCALABILITY PROJECT: In the introduction, you redefine or expand the definitions of the terminology in Feral Atlas. You speak about an “atlas” as a mapping device of nonhuman entities. “Feral,” as you describe, is not a negative or a positive judgment, but rather a description for something beyond human control. Together, this pairing, “feral atlas,” feels like a provocation. Could you expand on how we might use Feral Atlas as a verb?

TSING: Our goal was to show people that everywhere around them these feral phenomena are parts of our lives. If we were to think about feral effects—that is, the non-designed effects of infrastructure around us—we might have a really different take on what kinds of worlds we want to build. Using Feral Atlas as a verb is a way of trying to pay attention to all of those things.

This means that the challenges that are around us could be addressed in relation to the kinds of ecological effects that threaten to make this world an unlivable place. Sometime in the last year, our president allowed the unlimited spraying of antibiotics on crops, though there wasn’t any reason for this. This will make for a new strain of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Every time that kind of policy goes forward, we can use Feral Atlas as a verb to think about what we are creating with this process.

SCALABILITY PROJECT: On the website, these phenomena are shown as interconnected stories. How do you create the connections within Feral Atlas?

TSING: In the atlas, we try to create connections across many axes so that people can jump from one report to another. And so we have three primary analytic axes by which that can happen. [ see INDEX in Guided Tour ]

One is the historicity of programs of infrastructure making what we call invasion, empire, capital, and acceleration. For example, we can start with coronavirus but end up with plastic bags.

The second axis is formed by the Tippers, which have to do with the kinds of work that certain types of industrial imperial infrastructures create. Tippers take traditionally ordinary ways of doing things and highlight the brutality in them that hadn’t been clear before.

The third axis is made up of Feral Qualities. These have to do with the agency and activity of nonhumans. The way they get tangled in these infrastructures and become something completely different than they were before as a consequence of that entanglement. For example, when accessing the website you might be reading about water pollution of a particular kind, and a poem about stream pollution might put this into a different context.

SCALABILITY PROJECT: While reading and experiencing the website, we started to recognize patterns of these phenomena you are describing. Everything became interconnected.

TSING: In each case, something in common can be found within the agency of the nonhuman elements. Some are organisms that have a rapid evolution in response to human infrastructure, such as diseases. We want to show the way these cross scale—comparisons, juxtapositions, and overlaps done by users are continually moving, so nothing is an isolated story. This is a story about infrastructural work through which we’ve let the world become unlivable.

I think I’m going to argue against “growth” too, as maybe the word, but there have got to be other words that we could think about that have to do with the multiplication of the tentacles, as it were.

SCALABILITY PROJECT: You speak about infrastructures and how they inherently generate feral effects. Do you think we could create infrastructure that’s intended to promote these emergent behaviors, rather than allowing them to happen unintentionally?

TSING: It’s about paying attention. One of the most terrible things about capitalism is that distant investors have a whole lot to say about the fate of humans and nonhumans in some places that they don’t care about at all and they don’t stay around to figure out the terrible effects. Once a place stops being profitable, they leave a complete wreck. This method of organizing the earth is inherently irresponsible for those who live here.

SCALABILITY PROJECT: adrienne maree brown calls this “masculine action culture” 9 —entering a foreign space, making some big action, and then leaving. Similar to your “arts of attention,” she also encourages “critical connections over critical mass” 10 as a way to invest time and deep connection into a community, rather than profit-based incentives.

TSING: The idea of “bigger is better” is often wrong. There’s a part of the modernist set of assumptions that allows people to come up with plans as if they had no effects. Maybe the most important thing about using Feral Atlas as a verb is to consider the non-designed consequences alongside those that you want to happen.

SCALABILITY PROJECT: In a way, the action that’s required is an injection of time in the process that gives us the opportunity to pay attention. This could connect to Isabelle Stengers’s “slow science.” 11

TSING: Maybe we should think in terms of degrowth in certain areas, right? Sometimes growth gets in our way. There’s a lovely book by the anthropologist Julie Livingston called Self-Devouring Growth: A Planetary Parable. 12 In 150 pages, she argues that growth can become a way of undermining livability. Botswana is seen as an instance of successful modernization in Africa, yet the introduction of a commercial cattle export there funneled all of the water to ranches. Ordinary people had no water and public health was destroyed to support this “growth” sector of the economy.

SCALABILITY PROJECT: It’s really about how we plan things.

Feral Atlas is a very lofty and extensive collaborative project. We’re curious: How do you imagine others will contribute to the atlas? How will it grow?

TSING: My dream is that subsidiary websites would start up through which people would start telling their own Feral Atlas stories. By making them available online, we could create links between these projects. We had to cut it off in March for our final due date, but people were coming to us and saying, “I’ve got a story for you that really belongs in there.” And they were right.

I very, very much hope that there’s a way that these stories can keep coming out in community groups or in classrooms and that people can use this in our dream world.

SCALABILITY PROJECT: I love that—it’s one of the quotes that we highlighted in your book The Mushroom at the End of the World.

TSING: Exactly. “In this kind of storytelling, stories should never end, but rather lead to further stories.”

Guided Tour by Anna Tsing

Most discussions about the Anthropocene are about the planetary, and there’s nothing wrong with that, but it also silences the many different voices and different phenomena, the different histories, the different forms of structural violence that are going on. Feral Atlas compiles a series of field reports from natural scientists, social scientists, artists, and poets with a commitment to the empirical. This is not only a conceptual exercise. It’s a digital application to juxtapose and move horizontally across these stories to see the layered effect that they have on each other. It’s an exercise in scale.

Because scales are incompatible with each other, we can zoom in and out. We’ve tried to use the concept of the map to show how varying scales can be important depending on which issue you’re trying to see. We have process maps, a bullfrog jumping out of its enclosure. We have maps like railroad embankments that show the flow of water and what blocks it. The very diversity of our maps is a contribution to thinking about the Anthropocene as a term the way that I used it in Mushroom, as “a cascade of stories,” rather than as a single scalar effect that can go up and down.

HOMEPAGE

On the homepage, you’ll see our feral entities, such as a coronavirus spike protein, marabou storks, antibiotics with a little bacterium, and rabbits. When you click on one of these, it takes you to what we call an Anthropocene detonator landscape. This is a mining landscape with overburden on it, including diseases.

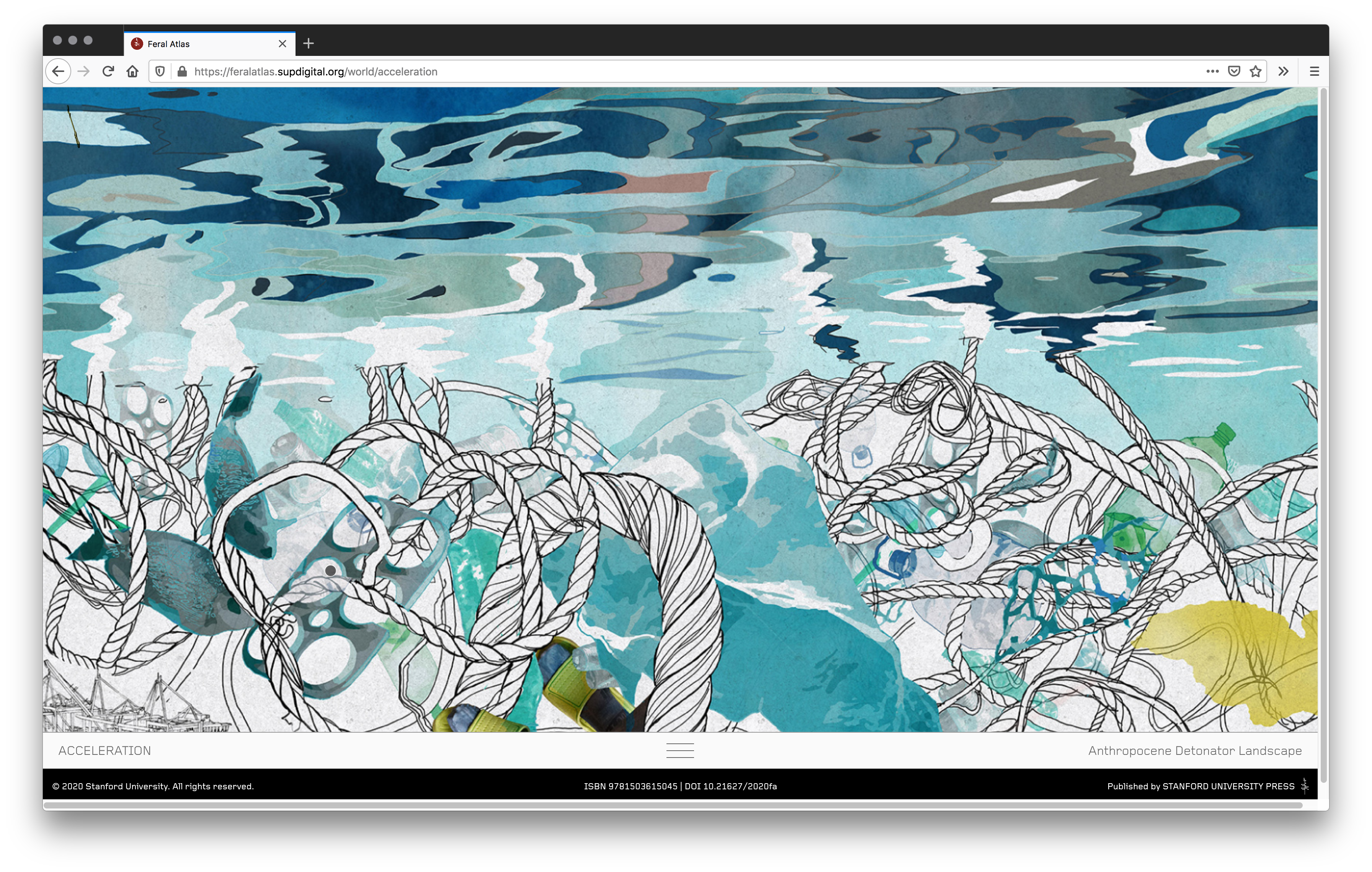

ANTHROPOCENE DETONATOR LANDSCAPE

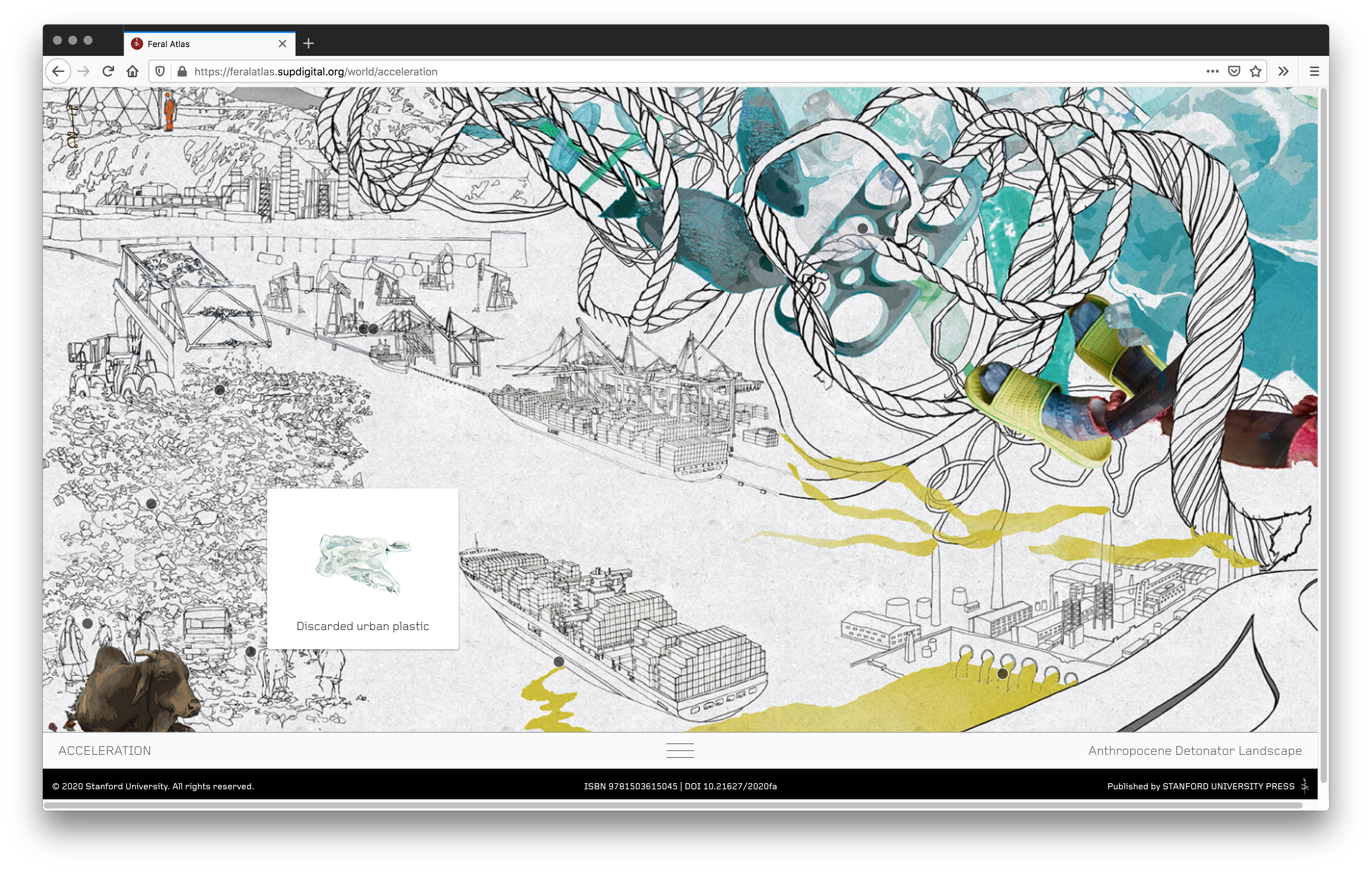

This is Acceleration, one of four Anthropocene Detonator landscapes along with Invasion, Empire, and Capital. You see many different scales, like the marine trash (pictured here), industrial pig farm, a suburb with sewage This is just one of four landscapes, and you can see the users are supposed to play in them to get a sense of the stories that are embedded in here. You see us playing with scale across time and space.

ENTITY

As you pan, you’ll find entities scattered around this landscape. There are many antibiotic-resistant bacteria, radioactive wood chips, brown plant hopper, green revolution rice, and phosphorous agricultural runoff. This is supposed to show our idea that an industrial or imperial infrastructure is interacting with an entity, in this case, discarded urban plastic (pictured here).

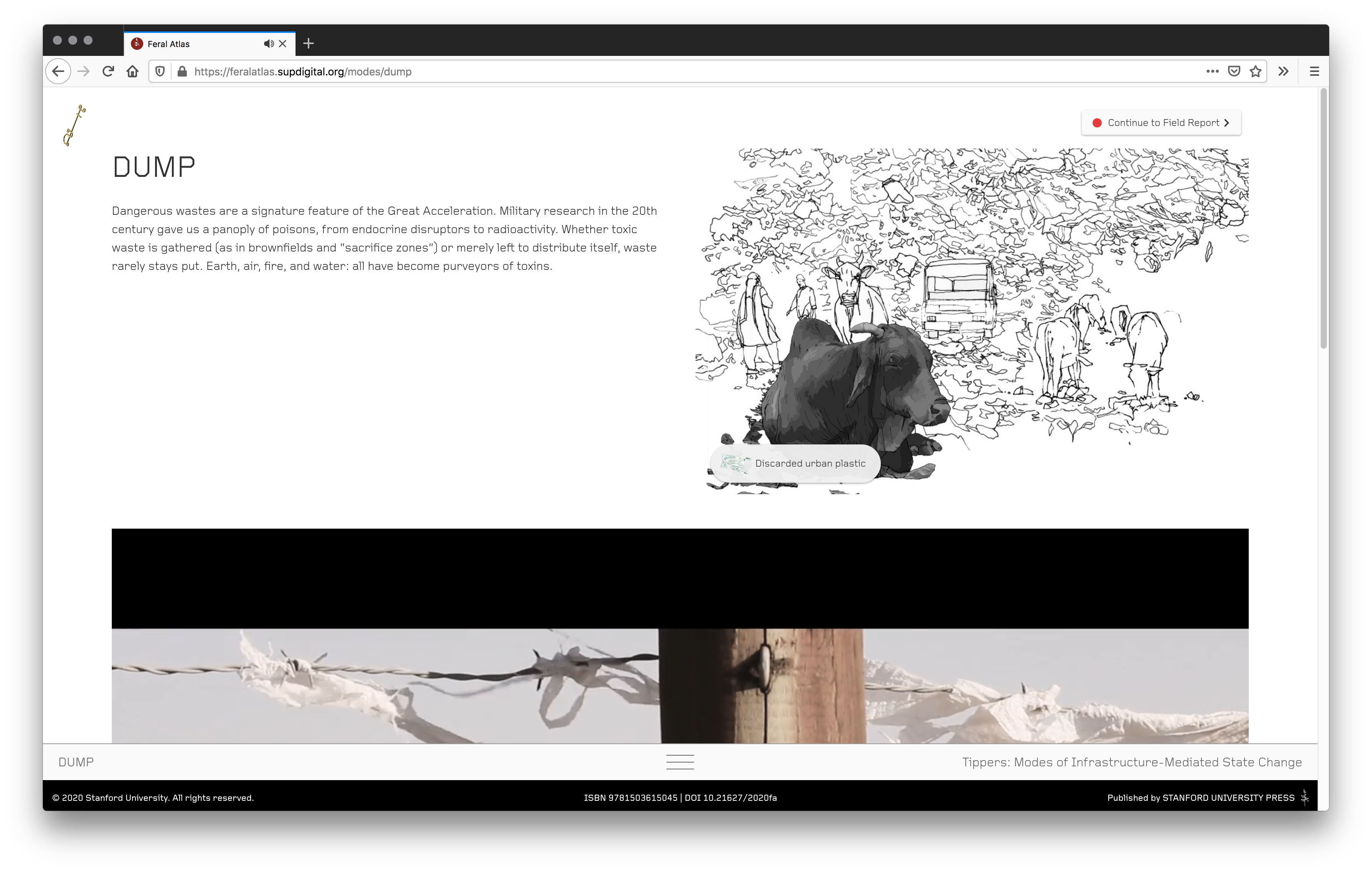

LANDSCAPE

When you click on “discarded urban plastic,” you’re taken to the dump, which includes a series of little videos. We argue that certain kinds of work are being done that changes the relationship between the landscape and these feral entities.

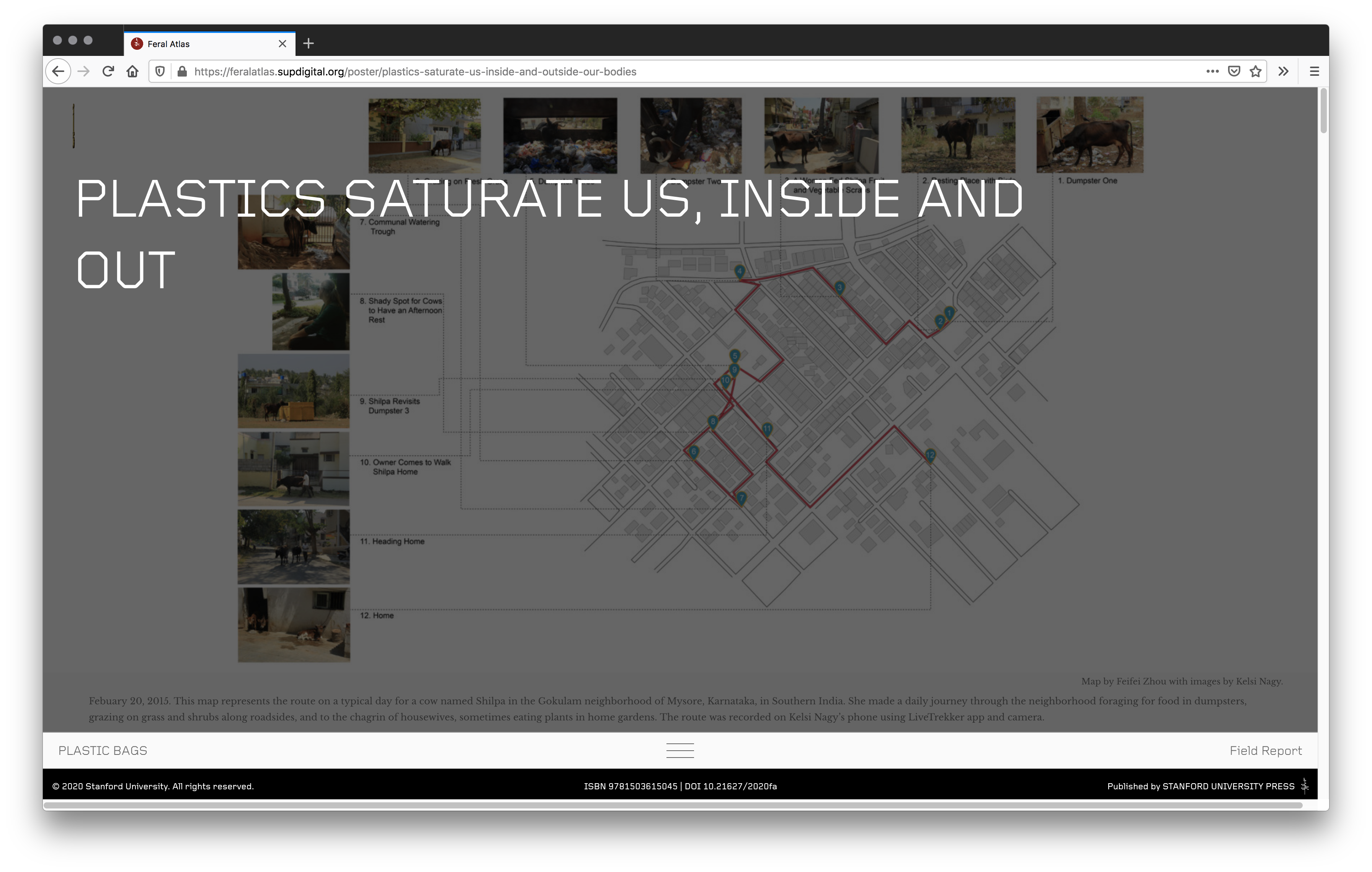

FIELD REPORT

If you continue to the field report, in this case, it’s a geographer who has written the story about plastic, “Plastics Saturate Us, Inside and Out,” She used her phone to take these pictures of one day in the life of a particular cow in a city in India. Owned and cherished, cows are allowed to walk around the city all day long. There’s a dairy industry there, and people think it’s particularly healthy to have the milk from local cows, but the cows are also eating food that’s in plastic bags. And so, the local milk is laced with plastic. She found, in fact, that cows prefer eating food found in dumpsters to green grass because it has more concentrated calories.

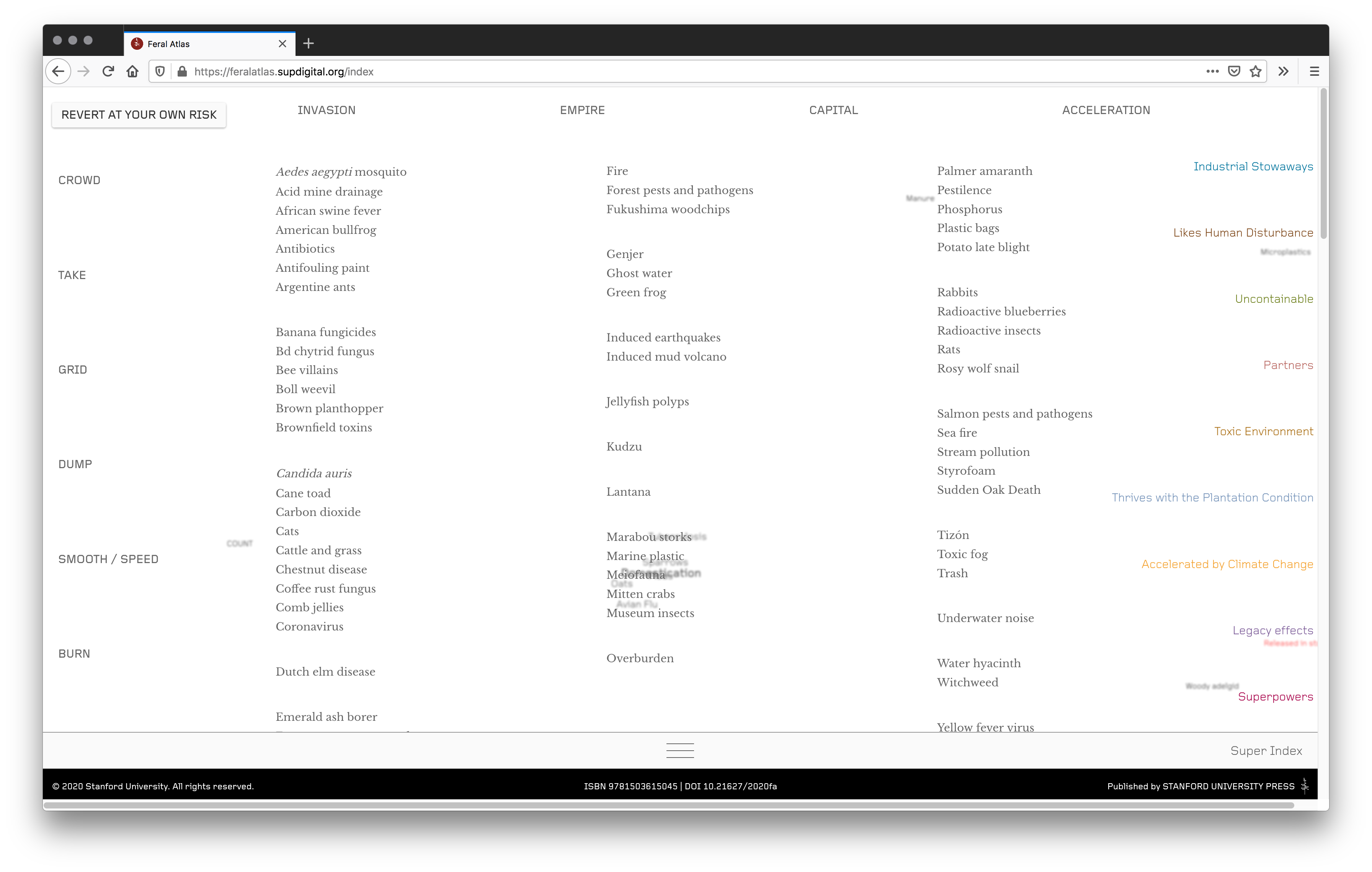

INDEX

This is our interactive super index. It includes essays and materials that you can read to understand these connections. On the top of the super index, we can find the Anthropocene Detonators. On the left side of the page, we find the infrastructure-mediated Tippers. On the right, we find the Feral Qualities, which include the actions of nonhumans.

FIELD REPORT

Another example shows the making of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. At first, they’re stopped by the presence of antibiotics. But we’re already getting mutations. And this is why the antibiotics we’ve come to rely on will stop working in the very near future—they’re increasingly drug resistant.

Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, 2015↩

Le Guin positions the container, rather than the spear, as the first human tool, following the writings of Elizabeth Fisher. Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 1986↩

In “On Non-Scalability,” Tsing establishes that a primary critique of scalable frameworks is of their inability to maintain diversity. Taking that intrinsic flaw into account, we aim to not promote the amplification of a singular feminist framework. Anna L. Tsing, “On Non-Scalability,” 2012↩

In an interview with Jorge Cotte, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun states, “Every form of communication is based on a fundamental leakiness.” These leaks can be seen as moments of possibility. Wendy Chun, “Reimagining Networks,” The New Inquiry, 2020↩

Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, 2015; Anna L. Tsing, Roxana Fabius, Patricia M. Hernandez, Mindy Seu, “Big histories are always best told through insistent, if humble, details,” The Scalability Project, A.I.R. Gallery, 2020↩

In Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell sees the glitch as a catalyst rather than an error, a “correction to the machine.” Legacy Russell, “Digital Dualism And The Glitch Feminism Manifesto,” Cyborgology, 2012↩

Here we are drawing from Judy Wajcman’s definition of interpretive flexibility. Wajcman describes technology’s malleable character, emphasizing that there is nothing inevitable about the way technologies evolve. Users have the power to radically alter technologies’ meanings and deployment. Judy Wajcman, TechnoFeminism p.37↩

Anna L. Tsing, Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, 2015, p.111↩

adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy, 2017, p.61↩

adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy, 2017, p.3↩

Isabelle Stengers, “Another science is possible! A plea for slow science”, 2011↩

Julie Livingston, Self-Devouring Growth: A Planetary Parable, 2019↩