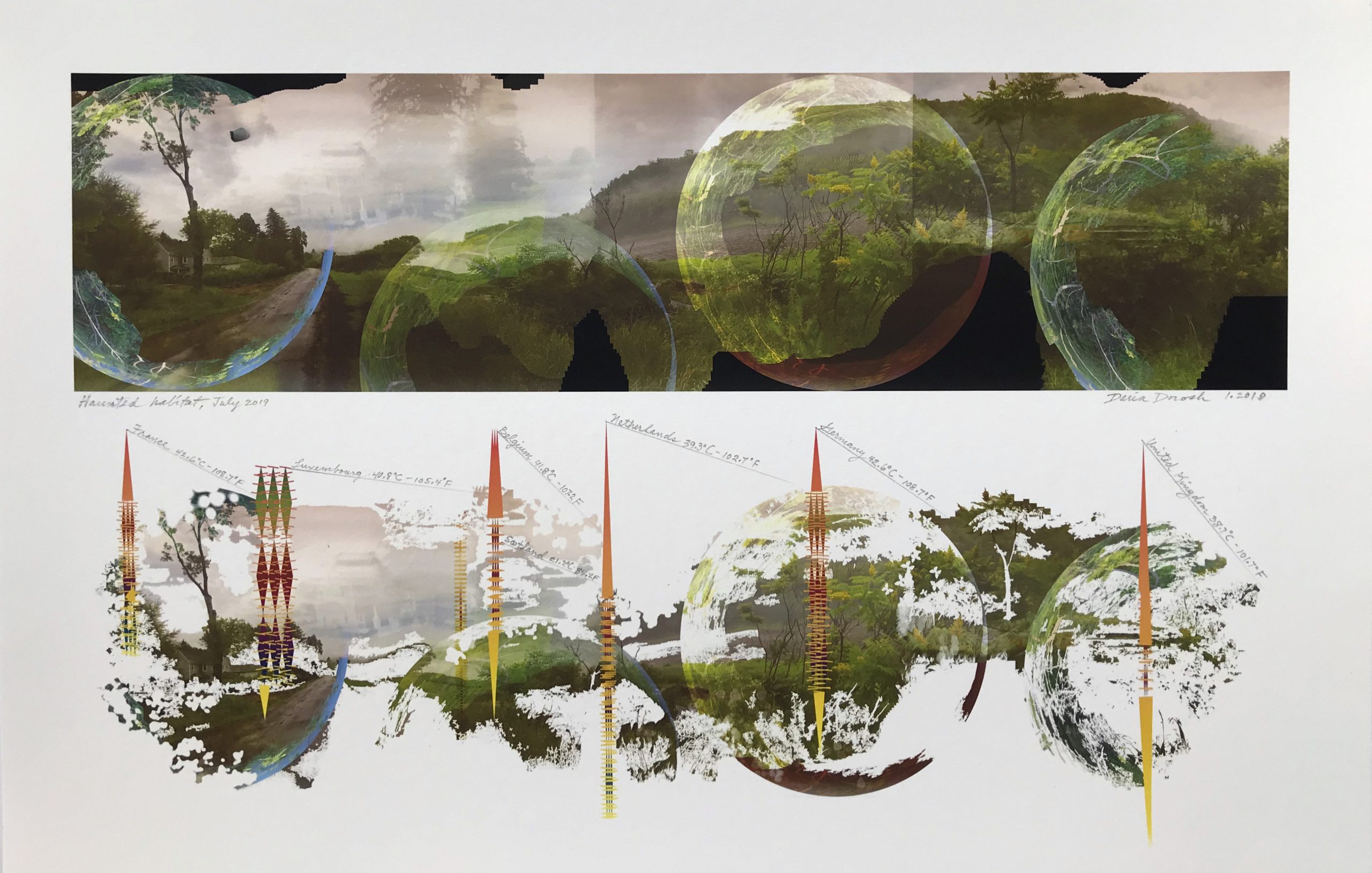

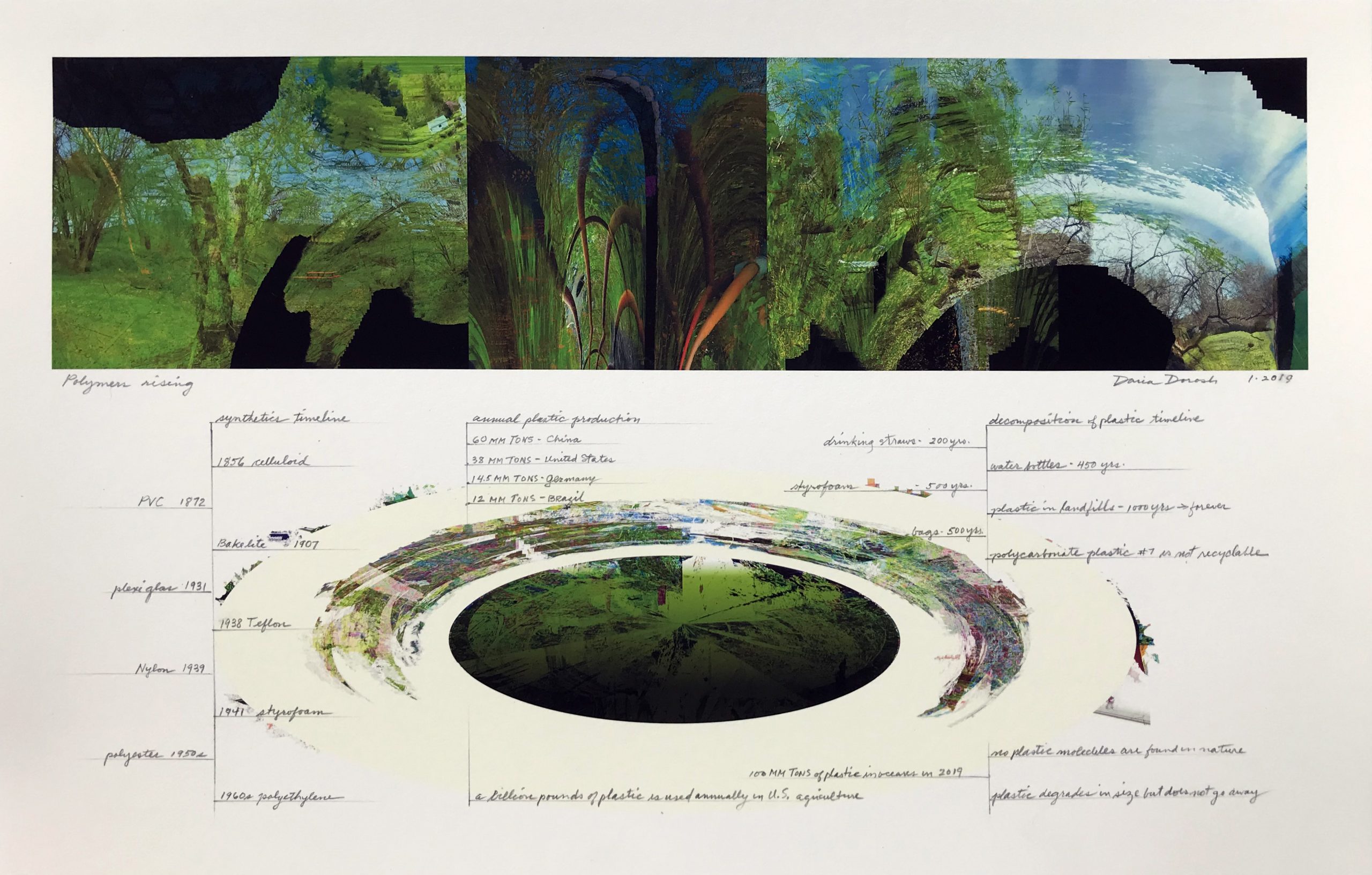

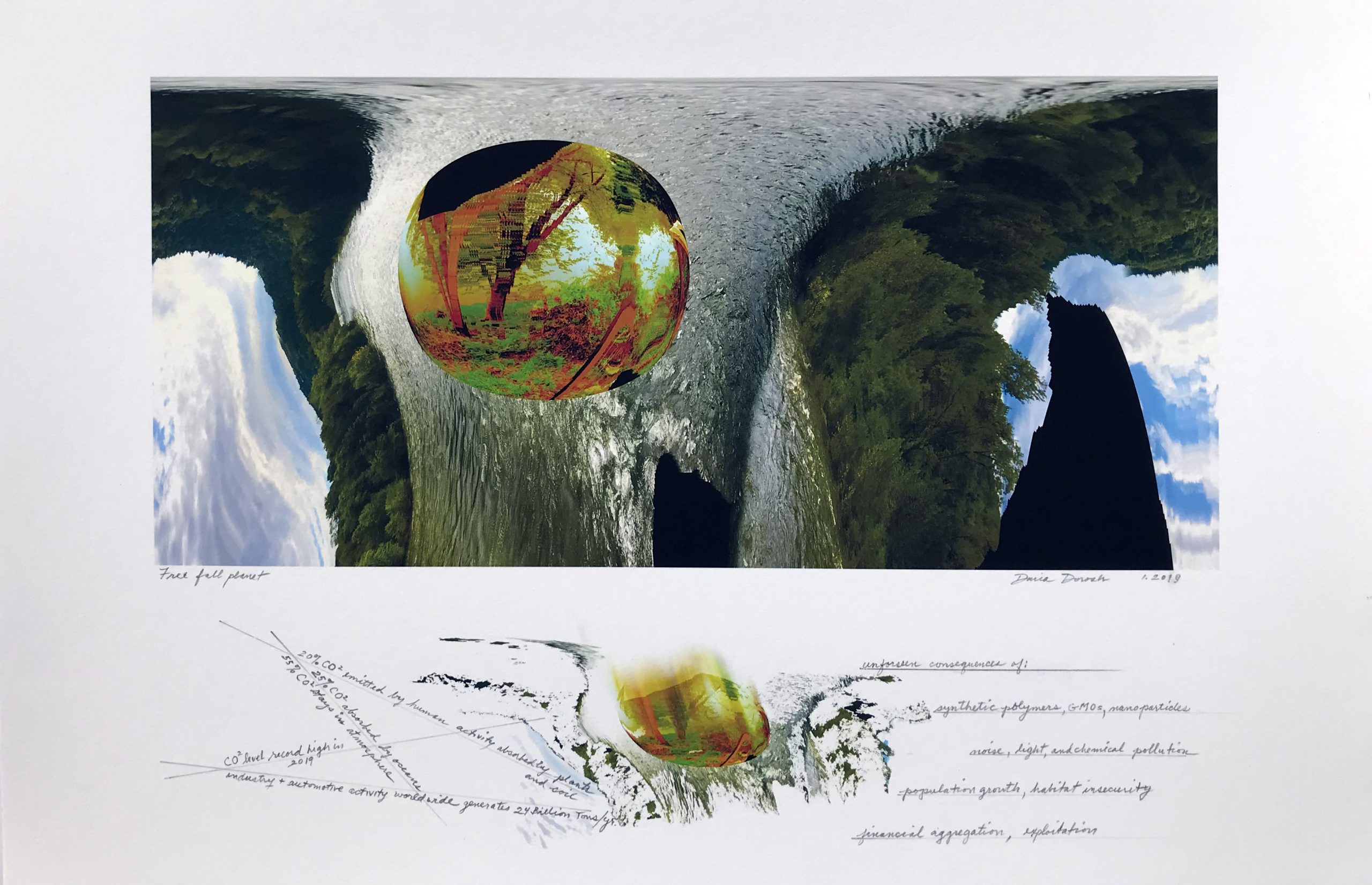

From its origins in 1972, A.I.R. has continued to be a space in constant flux, responding to the needs of both the community of artists it anchors and its surrounding sociological context. In an interview with Paddy Johnson in 2011, Daria Dorosh, one of A.I.R.’s founding members, described the gallery’s early community as made up of “artists who happened to be women with different skills of all kinds… We, as an organism, were an aggregation of those skills.” On January 11, 2021, we reconnected with Dorosh to discuss her career arc and involvement in this community. She told us about how she experienced the power of groups through the gallery’s history and, noting the organization’s multigenerational membership today, reflects on the role of evolution and legacy. Here, we’ve paired the conversation with a few of Dorosh’s drawings about hybrid networks, what she calls “communities based on difference instead of similarity,” from her latest series of prints, Interrupted Landscape.

Daria Dorosh is an artist, educator, and activist. Born in Ukraine, she has lived and worked in New York City since 1950. Dorosh examines cultural patterns that appear across disciplines, creating artworks that span painting, fashion, textile, video, and writing. Her current works champion the need for hybrid networks, pushing beyond the self-referentiality of homogenous groups.

— Roxana Fabius, Patricia Margarita Hernández, Mindy Seu

Interview

Haunted Habitat, 2019

Scalability Project: Can you speak about how the collective experience you witnessed at A.I.R. through the years can be translated to and replicated in a digital sphere? How can it be done to contaminate?

Daria Dorosh: There is a direct lineage from the analog collective to the digital in that both make space for the “other” and for diversity in whatever form it takes. It’s clearer to me now that the question was always about recognizing the necessity of difference. It could be said that A.I.R. contaminated the art world by insisting on a place for women within it. I’ve often said A.I.R. is my research space. At first, group dynamics were both an attraction and repulsion for me, because I didn’t trust them. I’m an immigrant and I’ve never gotten over being displaced; I’m always searching for some foundation. New York City was where I created my new home.

I think I was a feminist from the beginning. The freedom and diversity of A.I.R. was a very important thing to experience. There was no single art movement in the collective. People had different dreams. People had different abilities. Many of the initial artists, including the founders, left very early on. I found the idea of continuity really exciting, and for a long time, I never missed a show, never missed a meeting. A.I.R. was a wonderful training ground for self-sufficiency and collaboration. It helped me see that group experience could be positive when competition was not the driving force.

A.I.R—or any organization that values difference—is a place where nobody owns you. You can be whoever you need to be, and you can do it surrounded by others. You can choose the depth of your relationships with others in the group and which topics you want to put your energy into, and you can learn how to tolerate topics that may not be as satisfying. So here I am, forty-nine years later, still waiting it out. I’ve seen some dreams come true. I think we have the tools—and it’s exciting that we have the space—to come together as artists, to find smart people to help us, and to build a community around us so that we can hold onto this space for as long as anyone needs it, now or in the future. This is becoming A.I.R.’s legacy.

Polymers rising, 2019

SP: Could you tell us about the organization’s dynamic and about how your role has developed over the past fifty years?

DD: A.I.R. has changed a lot, especially in the last few years. The culture around us has been changing much faster than before. In the beginning, A.I.R. was a very simple model that actually worked. The freedom to chart our individual art journey, to create a space and to share it with each other, seemed to me at least, to be everything I needed to make my work. It was a safe place. We inadvertently shaped history at A.I.R. without any outside influencing factors such as economics or fame. A.I.R. is a messy space. It’s a space that will not be one hundred percent satisfying for everyone, but it’s one where we can be free. It’s a space of dialogue; we have to listen to each other, even though it’s painful sometimes. I think A.I.R. is a process, a relationship that keeps changing as artists and staff come and go. The operational structure allows for flexibility and new voices to emerge that keep it alive with new challenges.

Members can work together to initiate public projects. In the 1980s, Mary Beth Edelson and I created the “One-on-One” program, a lottery that paired a critic with an artist for a studio visit. Another project we did was the curated slide sets we offered to universities that needed images of artwork by women for their classes on feminism. In 1998, I met Judy Moncreif and Helen Golden, two artist-printmakers who helped me coordinate the first wide-bed-digital-print workshop and exhibition for women artists at A.I.R. This event introduced many women artists to large-format digital printing and led to discussions about the then-new technology for artists. More recently, the impact of the self-identified gender revolution on A.I.R. was really fascinating to witness, since our entire legacy was built on a definition of women that was socially constructed to exclude people. It was hard for women of my generation to get our heads around this new way of thinking because gender was our bedrock. And now we had to rethink gender for ourselves.

My analog generation grew up in a binary system of opposites, such as male/female, good/bad, white/black, abundance/scarcity, commercial/cooperative. Women artists were excluded from art history based on a gender bias that permeated all institutions including museums, galleries, and universities. This binary system was very pervasive. I believe it overshadowed our ability to imagine a non-binary world. But all of this changed with the digital desktop, which activated a postmodernist, either/and/or world, based on diversity, inclusivity, generosity, and collaboration, to survive. I believe feminists will have to dismantle that binary culture wherever it moves.

Another aspect of A.I.R that I find exciting is the multigenerational character of the current membership. We have an opportunity to expand diversity across time as each of us is plugged into a different historical moment, with different sets of information. I sometimes see my role as mentor to artists who are my colleagues at the gallery but at a different point in their art journey. I offer an observation about some aspect of the gallery from a fifty-year perspective that might inform current issues important to a new member. I try to share my belief that an artist’s legacy is a gift to a future culture. On the other hand, I am interested in new questions and in what the younger generation of artists cares about, because it influences my decisions about my future plans. Diversity across the boundaries of time and space is a rich repository of information that, in this kind of collective, we can access together.

Free fall planet, 2019

SP: A.I.R. has continued to adapt, combining the artifacts of the past and responding to the present’s current demands. You often talk about needing hybrid networks in which two or more different networks connect to a particular site to transform future outcomes.

DD: Yes, I champion hybrid networks every chance I get! From my experience, I think these are the ways we will find new patterns to live by. For me, being in a hybrid network means being in a community based on difference instead of similarity. Artists talking to artists, what we can accomplish is limited, and I think that’s true for every self-referential discipline and group. Both the Impressionist movement in art and the sportswear movement in fashion responded to the same scientific and mathematical patterns. That’s how I read what’s happening in the world and in my art: I need to look at patterns across differences to understand the processes taking place.

In 2002, I read Steven Wolfram’s A New Kind of Science, in which Wolfram visualized his scientific theory with patterns. This made his work accessible to an artist like me. With his Wolframtones, again, I saw how coding operates: I could compose a soundtrack for my videos with his mathematical cellular automata patterns. In the fashion world, people didn’t understand that art and math shared patterns. And so I went to Shima Seiki with a mathematician and said, “Look, why don’t we map our math patterns on your knitting machine?” I thought that we could discover a whole new purpose for clothing if it became a hybrid space of science, education, fashion, and technology. And we did: we programmed the software for their machines to create knit patterns that came out of Wolfram’s theory. I love walking into places where I don’t belong. Infiltrating other networks is important because we need to have each other’s information.

SP: After this very sedentary, virtual year, can you expand on how or if digital correspondence might become a private or public space that generates hybridity?

DD: The invisible space we share has powerful possibilities. When I made art for public spaces in the eighties and nineties, I felt like I could do anything I wanted, sometimes using the city as my studio without permission. Today, Zoom space really interests me because it appeared in our lives rather suddenly and in a very big way. At first, I approached it thinking, “Oh, look, we’re not using it as a public space? Should we be?” Every time I’m on Zoom I see someone’s personal living space. It feels like intimacy without consent, but we all seem to be disregarding this sense of intrusion. Is it because we don’t know if any social media is public or private? Or perhaps those of us who were born digital have no idea that there was once a difference.

People are doing crazy things on it without realizing that it’s a public space. I’m an artist who is interested in creating a sense of place. With video correspondence, you’re unable to make eye contact with the person you’re talking to. Digital communication does not have the full spectrum of energy that we normally exchange. If we’re going to be stuck in this space, how do we take it back as creative people? Is anyone else noticing that we’re becoming tragically mono-focused on ourselves? We miss the interaction, vibrations, energy from other people that sheltering in place with one person does not fully satisfy— though being digitally connected expands our options and knowledge about the world and ourselves in a way that feels necessary. I think that as a presentation/publication model, The Scalability Project and Feral Atlas are two examples of fabulous new forms of curatorship —each a sort of a hybrid book, art space, think tank, and open-question space. Both are virtual growth spaces filled with possibilities.

Megacities rising, 2019

Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, 2015↩

Le Guin positions the container, rather than the spear, as the first human tool, following the writings of Elizabeth Fisher. Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, 1986↩

In “On Non-Scalability,” Tsing establishes that a primary critique of scalable frameworks is of their inability to maintain diversity. Taking that intrinsic flaw into account, we aim to not promote the amplification of a singular feminist framework. Anna L. Tsing, “On Non-Scalability,” 2012↩

In an interview with Jorge Cotte, Wendy Hui Kyong Chun states, “Every form of communication is based on a fundamental leakiness.” These leaks can be seen as moments of possibility. Wendy Chun, “Reimagining Networks,” The New Inquiry, 2020↩

Anna L. Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, 2015; Anna L. Tsing, Roxana Fabius, Patricia M. Hernandez, Mindy Seu, “Big histories are always best told through insistent, if humble, details,” The Scalability Project, A.I.R. Gallery, 2020↩

In Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell sees the glitch as a catalyst rather than an error, a “correction to the machine.” Legacy Russell, “Digital Dualism And The Glitch Feminism Manifesto,” Cyborgology, 2012↩

Here we are drawing from Judy Wajcman’s definition of interpretive flexibility. Wajcman describes technology’s malleable character, emphasizing that there is nothing inevitable about the way technologies evolve. Users have the power to radically alter technologies’ meanings and deployment. Judy Wajcman, TechnoFeminism p.37↩